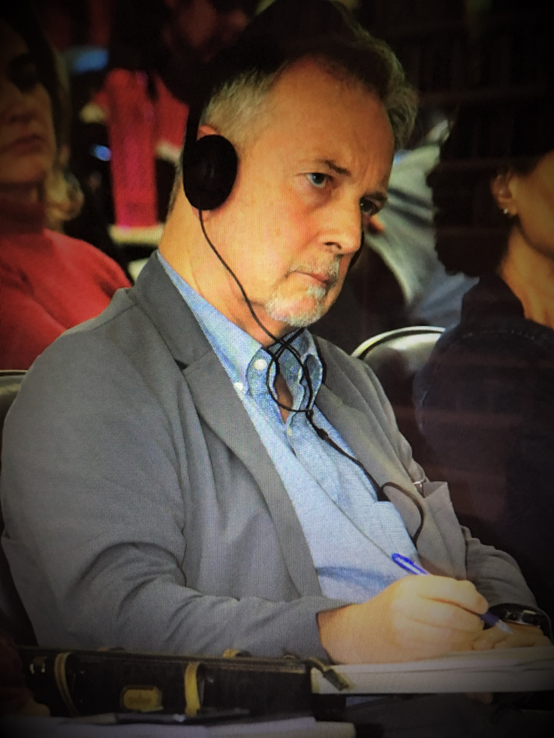

Many leading Cypriot jurists studied at the University of Exeter, amongst them Dimitrios Hadjihambis, Takis Eliades, George Savvides, Haris Boyadjis and Giorgos Serghides. For nearly thirty years (1979-2009), another Cypriot, Kim Economides taught at the University of Exeter, in various capacities. From 1999-2004 he was the Head of Exeter Law School, whereas from 1989-1993 he was Director of the Exeter University Centre for Legal Interdisciplinary Development. Following his retirement from Exeter, he became Professor of Law and Inaugural Director of the Legal Issues Centre at the University of Otago, New Zealand (2009-2012) and then Dean of the former Flinders Law School (2012-2017).

A Professor of anthropology of law and sociology of law, as well as legal ethics, in recent years he has focused on access to justice and policy-oriented law reform in which he applies socio-legal, interdisciplinary and comparative methods to explain legal behaviour, with particular reference to civil disputes, professional regulation, rural legal services, legal education/skills and legal technology. Kim has been well-respected in legal circles, having served, inter alia, as President of the International Association of Legal Ethics and General Editor of the Legal Ethics journal, and Vice-Chair of the Socio-Legal Studies Association, as well as Series Editor of The Hamlyn Lectures. Very active in legal reform as advisor to the Law Society, and Parliamentary Committees, he has been for the past semester in Cyprus, a country which is in desperate need of legal and social reform.

1.What is the work you are currently doing in Cyprus?

This semester I have been teaching Sociology of Law and Research Methodology on a part-time basis at the University of Cyprus (UCY) and hope to return to Cyprus more regularly now that I have retired from being a law dean and full-time law professor in Australia. I am also working on improving my understanding of Cypriot legal culture and the legal system here with a view to conducting or contributing to future research projects examining the operation of civil justice and dispute processing in Cyprus. I am also re-connecting with senior Cypriot lawyers, judges and politicians, many of whom studied Law during my time at the University of Exeter, while learning more about the work of Cypriot lawyers and judges, and in particular the challenges they confront, both now and in the future. In short, I am here to teach, learn about law in contemporary Cyprus while also improving my command of the Greek language.

2. You have had a lengthy career in various common law jurisdictions with special emphasis on policy-oriented law reform. What would be your advice for Cyprus which is struggling with access to justice considerations?

I have also spent some time in civil law jurisdictions – including three years in Italy at the start of my career when I worked on the Florence Access to Justice Project – and more recently in Brazil where I have also been working on problems of access to justice collaborating with Brazilian researchers. I am hesitant to give definitive advice when I still have only a partial understanding of the complex issues connected with law reform here in Cyprus, which has an interesting hybrid legal system. Too often I have seen that quick-fix so-called ‘reforms’ either exacerbate – or just transfer elsewhere in the system – the very problems they are supposed to solve, and therefore I prefer to open up channels of communication between various stakeholder interests who share a common concern about the future of the justice system. This is essentially the idea behind my proposal for a new Cyprus Justice Agora that I recently put forward at a research seminar at UCY. In my view, there needs to be much greater dialogue on the reform agenda itself as well as empirical research into the actual operation of the justice system. We need to do better than just rely on anecdotal evidence and personal experience, valuable as that might be, and learn more about the objective strengths and weaknesses of the current system. Identifying and measuring these characteristics is the real contribution of the socio-legal researcher. In my view a strategy for justice should be developed as an ongoing collaborative venture and, I suspect, there will always be a need to build more trust and mutual understanding between the relevant stakeholder interests (the judiciary, leaders of the legal profession, public servants in the Ministry of Justice and Attorney-General’s department, legal (and other) scholars as well as not forgetting consumers of the justice system, the wider public who must use and rely upon legal services. Better communication is the key to unlock the many doors that block citizens’ access to justice.

3. What about legal ethics? Has their importance been undermined in an era of intense competition amongst law firms? Is there a potential for further harmonization of legal ethics rule in Europe?

I have not looked closely at this issue here in Cyprus but evidence elsewhere suggests that increasing competition in the market for legal services can indeed have an adverse impact on the standard of legal work. But egregious conduct may have many causes, structural or behavioural, and I am sceptical about how much regulation can achieve in this area. Harmonization of rules of ethical conduct will achieve little if the underlying causes of misconduct are not addressed, and I should like to see a greater emphasis in legal education that occurs both in law school and Continuing Professional Development (CPD) that actively promotes good (moral) legal behaviour, rather than simply punishing poor conduct of lawyers through regulatory systems. An “Ethics Day” was recently held at UCLan where we explored the value of a legal Hippocratic oath/declaration/pledge at various points in a legal career that might help to instil and reinforce a deeper commitment to fundamental and/or professional legal values.

4. You are noted for your emphasis on socio-legal, interdisciplinary and comparative methods approach. Do you think the time is due for legal researchers to give more weight to empirical research, rather than black-letter analysis?

All are quite different yet valid ways of approaching and understanding law and, in my view, these contrasting approaches complement each other. To focus exclusively on any one is far too limiting and we need the particular insights that each has to offer. If the idea of a strategy for justice gains traction then socio-legal, comparative and interdisciplinary perspectives could well assist with developing an action plan to implement and monitor the impact of law reform. I would certainly not advocate abandoning traditional legal skills associated with the black-letter tradition – these are very important if not essential in order to be able to ‘think like a lawyer’ – but I do think more room needs to be made for other approaches to supplement traditional legal analysis, and precisely how much will depend on what issue is under consideration.

5. Technology is changing the legal profession. How do you feel that lawyers should respond to the technological innovation and especially the use of AI in law?

I would suggest lawyers respond to ‘innovation’ with caution and a measure of scepticism. There is a tendency to see technology either as some kind of panacea, or else as a Pandora’s box. Lawyers certainly need to stay alert to the opportunities and ambivalent impacts of technology, not all of which are benign, and there is no doubt that technology is changing the working environment of lawyers and how legal services will be delivered. Online legal services and courts are already here, and so is cybercrime. But I think there is a real danger in exaggerating this impact, good or bad, and I suspect that core legal values and functions of the legal process are far more stable and durable than some futurologists would have us believe. For decades now we have been told that the legal profession is moribund, that robots will replace lawyers and judges. Similar predictions are made for other professions and yet unemployment rates for the professions actually have not changed that significantly. It is true that expert systems may well be able to take over more routine aspects of legal work, as we can see now for example with e-discovery, but we are still some way off machines being able to replace the more creative or human aspects of legal work, especially the art of judgment or empathy in the lawyer-client relationship, and one needs to ask who is programming these machines and what resources will they draw upon? Solutions to the underlying problems and challenges that confront modern Cypriot lawyers are more likely to be discovered through a deeper engagement with theory, history and other legal cultures than any quick technological ‘fix’.

6. The Law and…’ movement has changed the landscape of legal studies and research during the past 20-30 years. You have done pioneering work in law and management studies and law and geography. How do you view the further development of the movement, especially in Europe? Do you feel it has been successful in bringing legal research in closer connection with society and other disciplines?

There has been progress but more work still needs to be done. It is now over a decade since I left the UK to emigrate to New Zealand, then Australia, and during this time I have not been following so closely European developments. I have been concentrating instead on understanding law from a (post)colonial Antipodean perspective, which is also relevant to Cyprus given that it too is a former British colony. Interdisciplinary approaches continue to expand and enrich legal scholarship and legal studies across many areas – indeed today it is hard to imagine any branch of learning that is not in some way connected with Law – and legal scholars still have much to learn from, and to contribute to, other disciplines. My latest research, drawing upon legal anthropology, explores whether advanced Western legal systems can do more to learn from First Nation and Indigenous perspectives. We need to question assumptions that, through legislative enactment, the supposedly more civilised Westminster model of governance can always come up with all of the answers. With so much uncertainty and confusion surrounding the farce of Brexit, I feel it is now time for the former colonies to take charge of their destinies and, drawing upon insights rooted in their local legal cultures that frequently emphasise our connection with the land and respect for the environment, identify how other conceptions of law and justice could assist with finding solutions to pressing social and political problems. Cypriot legal scholars might therefore consider a change in the focus of their scholarship to examine more closely the relationship between law and modern Cypriot society and perhaps draw more upon Cypriot culture and experience when developing legal principle. I would therefore call for a more inductive (bottom-up) approach to the development of legal norms instead of thinking exclusively about how Cyprus regulates (top-down) to implement and comply with international, European or colonial legal norms. Moreover, I suspect knowledge and insights rooted in Cypriot legal culture and experience could become a valuable resource, particularly when it comes to tackling problems of dehumanisation thrown up by globalisation and the technological innovation we touched upon earlier.

7. Can you tell us a few words about the Global Access to Justice Project you are currently working on?

Very briefly, this project which “aims to research and identify practical solutions to this “access” problem by forming an international network of scholars drawn from all over the globe, and on an unprecedented scale” currently has 171 participants, representing 98 countries, including Cyprus. A team from UCLan is preparing the Cypriot national report under your direction, as a Regional Co-ordinator for the Middle East and North Africa (MENA). I am the Regional Co-ordinator for Oceania, and Thematic Co-ordinator for Professional Legal Ethics and Anthropological/Postcolonial approaches that learn from First Nations Peoples, examining further the anthropological perspectives just mentioned. I suppose you might say this brings me full circle: having started my career studying access to justice in Florence, I now conclude it, still studying the very same issue, albeit from different perspectives and using different analytical tools.